Výpustek Cave - history

THE HISTORY OF THE VÝPUSTEK CAVE

The First Mentions and Explorations

The first mention of caves in the Křtinské valley comes from quack doctors and dates back to 17th century. In 1663 an educated monk called M. A. Vigsius described the Výpustek Cave as follows: “… within half a mile of walking in the corridor we come to an area where there is an abyss on the left. If you want to see how deep it is, throw a stone in but do not climb in there.” The danger of the Výpustek abyss is also mentioned by J. F. Hertod of Todtenfeld, a physicist from Brno, in his book “Tartaro – Mastix Moravie”. He says that “… in the cave there are holes leading to passages and abysses that nobody has dared to explore yet.” In 1807 the landowners – the Liechtensteins – had the Výpustek Cave mapped. The map made by the count engineer Anton Lola has not been preserved but in 1880 Josef Szombathy used the map as a source and completed it.

Visits of Count Hugo František Salm (*1766 – +1836) meant an important era in the cave research. He visited the underground labyrinth of the Výpustek Cave several times and claimed that it was bigger than the Sloup caves, which he had known well. He estimated the length of all premises as about 7 kilometres and stated he had used 3–4 sacks of chaffs without reaching the end. Salm also mentions that at the end of the 17th century 14 people from Olomouc died in the cave. They entered the cave but never came back. He is said to have had the most dangerous part of the cave walled up to protect other visitors from such danger. According to Dr. Jindřich Wankel there was only a 30-metres-long space behind the corridor Babická chodba. Wankel literally says that “Salm knew such places in the Výpustek Cave which only a few mortals have succeeded to see so far and which were later perseveringly sought after.” Wankel published the plan of the Výpustek Cave and its four abysses in 1882. Accompanied by a local worker (whose father took part in Salm’s research) he sought the place which had been walled up by Salm. The worker pointed with certainty to the corridor Babická chodba. Wankel tried to loosen the cave-in but he did not manage to find the fabulous spaces.

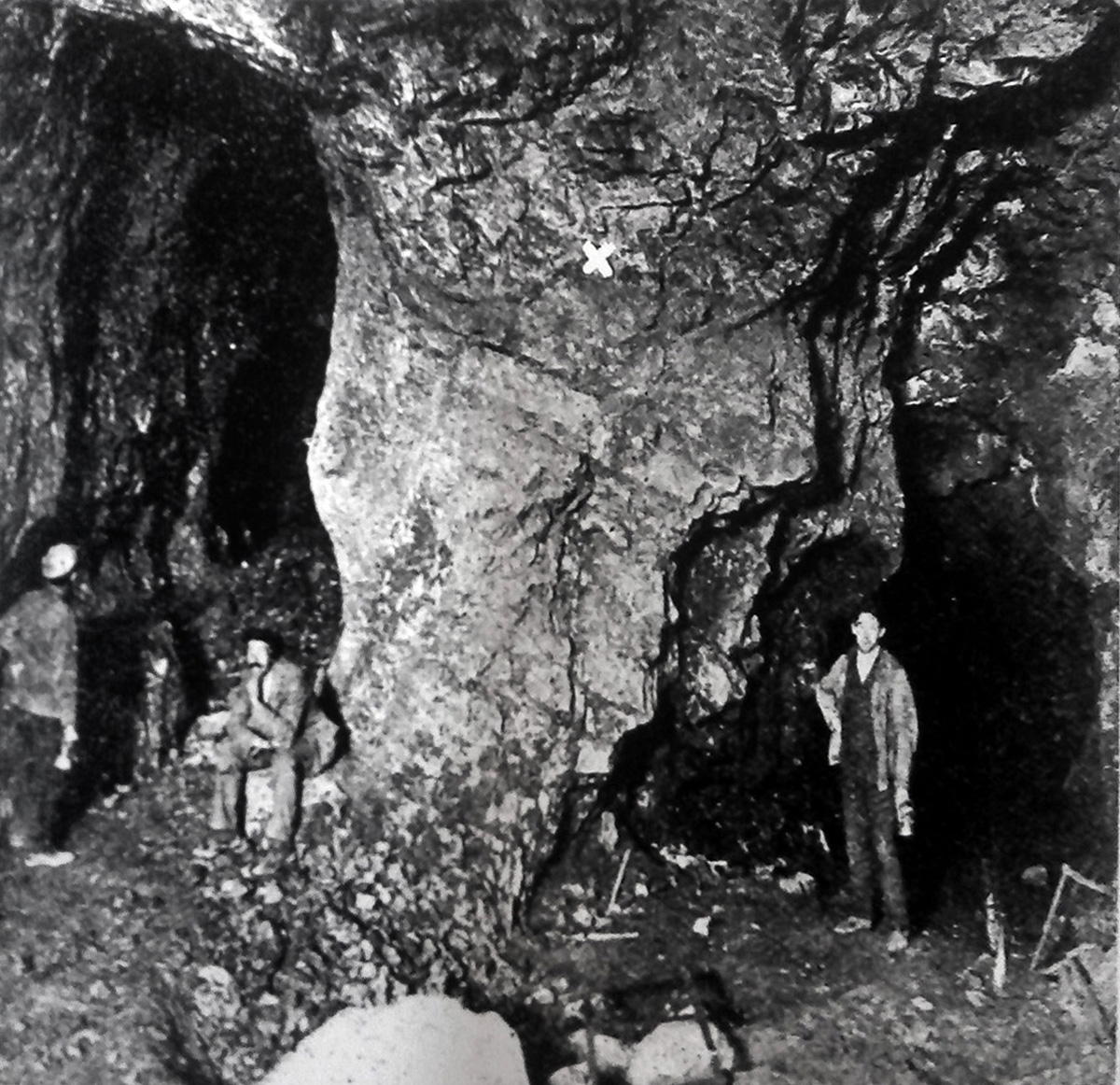

In the second half of the 19th century Dr. Martin Kříž and Josef Szombathy, a curator of Academy of Sciences in Vienna who made a few entrances to some abysses accessible, were engaged in research. An approximately 100-year-old skeleton of a sturdy man was found at the depth of 15 metres in the abyss No. 1, which is the nearest one to the entrance. One of the workers made a descent into the abyss No. 3 where, at the depth of 47 metres, he happened to find the groundwater flow of the Křtinský Brook. Szombathy also inserted probes into sediments rich in skeletal remains of Pleistocene fauna. In this way he acquired a collection which has been on display in the Natural History Museum (Naturhistorisches Museum) in Vienna to this day. There are e.g. skeletons of cave bears (Ursus spelaeus), the skeleton of a rhinoceros (Rhinoceros tichorhinus), skulls and bones of a cave lion (Panthera spelaea), cave hyena (Crocuta spelaea), horse (Equus sp.), wolf (Canis lupus), wildcat (Felis silvestris), ibex and small vertebrates – polecat, marmot, hamster and others.

The work of Ing. H. Bock, an Austrian citizen from Graz who worked in the Moravian Karst from 1902, is significant as well. He published the plan of the Výpustek Cave on a scale of 1 : 1000. His map corresponds with Szombathy’s plan. H. Bock together with O. Olbert made a brave descent to the third abyss. To get there they used a double rope with knots tied every half metre. At the depth of 35 metres they happened to find an underground stream and mapped the spaces.

In 1912 Bulla and Hope, members of the “Cave Research Group”, discovered one hundred metres long spaces behind the corridor Nízká chodba at the so-called “Prostřílené místo” (Riddled Place). This discovery was forgotten. The spaces called “Vysoké chodby” remain unknown.

Phosphate Clay Mining

At the beginning of the 20th century, a high content of phosphorus was found in clay fillings of the Výpustek Cave. The accumulation of animal bones and bat guano changed the cave clay into a quality phosphate fertilizer and its exploitation was launched in May 1920. The excavation of 6 metres of clay significantly enlarged the corridor profiles and many isolated spaces were connected. A narrow-gauge track was built in the cave. In front of the entrance there was a clay-preparing plant, which produced from 2 to 3 wagons of pure phosphate clay. Bones of Pleistocene animals excavated while mining were partly saved, among them six complete skeletons of the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus), which are now deposited at the Moravian Museum in Brno. Most findings, however, ended up in fertilizers.

Similarly, the mining devastated the stalactite decoration. A few archaeological artefacts as evidence of settlement during the Old Stone Age (Paleolithic Era) and the Aurignacian Era were saved from offloads.

Pre-war Research

In 1923 František Polák managed to enter the area behind the Babická chodba corridor. He probably rediscovered forgotten passages and abysses with exquisite stalactite decoration, which can be considered to be the most beautiful in the whole system.

The remote parts of the cave remain a mystery. A hand-drawn plan of discoveries from the year 1939 exists. Its author, Josef Urbánek, was said to have uncovered lower floors – a total of 560 metres of corridors – and a huge lake 128 metres long. The report was not discovered until 1947 and the cave area of Urbánek’s Výpustek has still not been found up to the present day. If it really exists.

World War II and Research until 1960

Urbánek’s map is dated 1939, thus two years after the Czechoslovak Army takeover. The cave was still devastated by its activity. Walls and projections on the ceilings were blasted out and trucks went into the cave. The Výpustek Cave became a military depot.

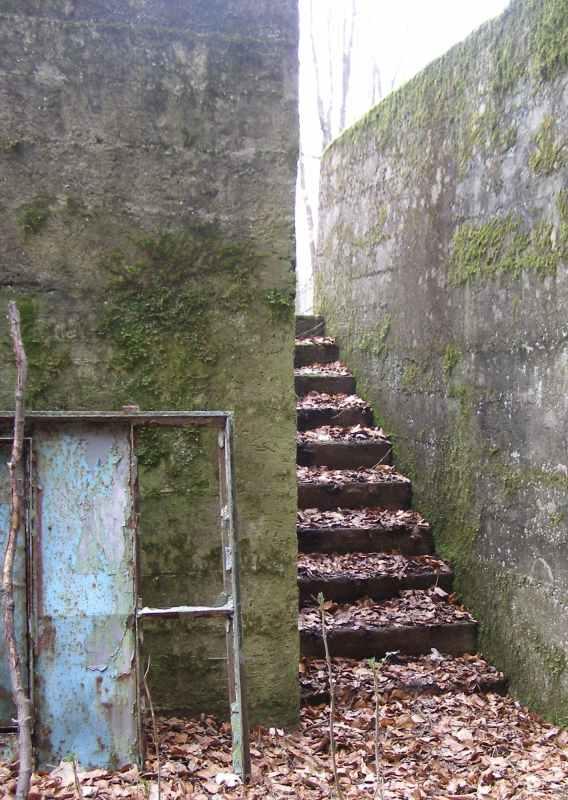

At the end of World War II the Germans established an arms factory there, which produced the components of aircraft engines. Layers of concrete covered the floor area. The side corridors were walled up, an underground boiler room was built and air chimneys were put through. Penthouses were hung up above a number of machines. Every day 1,200 workers and 120 clerks, mostly subjected to forced labour, took turns in continuous shifts. Since the Germans did not manage to evacuate the equipment while escaping, they set the structure on fire and partly blew it up using explosives. This completed the destruction of this unique natural phenomenon. The cave explorers managed to renew some entrances leading to side corridors and abysses. The Habrůvky group of the Speleological Club managed to get through to the area behind the Babická chodba corridor and found the signatures of F. Polák from the years 1923 and 1925. Despite detailed research, the areas allegedly discovered and mapped by J. Urbánek in 1939 have not been found.

Building of the Dugout and the Present Time

In the early 1960s, within the context of the international situation, the Výpustek Cave was retaken over by the Czechoslovak Army. Into the devastated premises they built a concrete structure to function as an anti-nuclear shelter and a backup command post of the Czechoslovak People’s Army forces in the following decades. The underground structure houses an independent energy source, transient decontamination chamber, air decontamination and air exchange equipment, survival supplies, bed compartment, and telephone and teleprinter connection. This “top secret object of special importance” including an extensive area above the ground was controlled and guarded by the army until 2001 when it was decommissioned from a state of combat readiness and unclassified. In 2006 the Cave Administration of the Czech Republic took over the Výpustek Cave and after some adaptations of the entrance area and the cave itself, the underground area was made accessible to the public. An exposition detailing the relationship between humans and caves is being gradually created here.